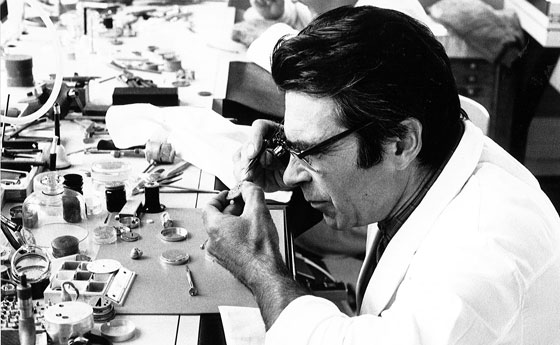

For two decades, Frank Vaucher was «the» precision timer at Longines. Today his archives are accessible to the public in Saint-Imier.

Richard Vaucher, son of Frank, deceased in 2007, said: «We didn’t want time to erase everything!» Five years later, in 2012, with his sister and other heirs of the late horologist, he bequeathed to the Jura Archive and Economic Research Centre (CEJARE) in Saint-Imier the heritage left behind by his father, an exceptional watchmaker who was a precision timer at Longines and a specialist in grand complications. Today, after a long and patient process of sorting, classifying, indexing and evaluation by the institution, Frank Vaucher’s records are accessible to researchers, watchmakers, specialists and enthusiasts eager to study the history of chronometry through documents conserved by this highly skilled precision timer.

«This collection is crucially important to our understanding of chronometry and precision timing in watchmaking firms, two areas experiencing a kind of renaissance, but also provides insight into observatory contests», notes Philippe Hebeisen, director of the CEJARE. The history of such contests dates back to 1790, with the first tests held in Geneva and the first ever chronometry contest in 1816, while the Neuchâtel contest for its part was staged for the first time in 1860. It was in these two «competitions», and especially the contest organised by Neuchâtel Observatory, that Frank Vaucher made his mark, winning no fewer than 28 Guillaume Awards (in recognition of truly outstanding achievements) with 265 chronometers (pocket or wristwatch) singled out by the institution.

A half-century of living history

The collected documents (sketches, reference works for training, general history of watchmaking, backgrounds of other firms in the sector, photographs, etc) cover the second part of the 20th century, and more particularly the fifty years of development of watchmaking techniques during which Frank Vaucher worked for his only employer, Longines, for 47 years. In the Saint-Imier firm, which he joined in 1947 after completing his apprenticeship at the city’s school of watchmaking, he spent time in all departments before becoming a precision timer in 1954. Between 1955 and 1969, he obtained more than 250 awards and records from Neuchâtel Observatory for the watches he timed. In 1966, he even set a «world record» with a mark of 1.72 in the category of pocket chronometers, which remains unbeaten to this day. During this period of more than 18 years, he also played a part in improving different calibres for the brand whose logo is the famous winged hourglass. «Of capital importance, these records allowed watch manufacturers to stand out from their competitors», says Pierre-Yves Donzé, a watchmaking historian and associate professor at the University of Kyoto (Japan).

However 1972 and the advent of quartz sounded the death knell for contests and timers alike. Frank Vaucher, whose qualities as an inventor and designer were recognised, took up a research role at Longines and moved subsequently to Special Fittings, before finally joining the firm’s Design department. He took charge of the preparation of watches for scientific missions, the finishing of complicated watches, the development of special features and the invention of calibres, and also worked on the legendary «Lindbergh». Nonetheless, with the watch industry crisis of the 1970s and the ensuing bankruptcies, many documents, together with much of the know-how possessed by these artisan watchmakers, simply disappeared. «Hence the importance of these archive collections, which bring together the annals of a talented individual with a global reputation and not simply the records of a company, as is generally the case at the CEJARE», notes the historian, who was the first director of the institution at the time of its creation in 2002. On the one hand, the Frank Vaucher collection retraces the exceptional career of a legend of chronometry, emphasizing in passing a new approach which saw the best timers hired directly by a single firm to form part of a regular team, as happened at Longines, Omega, Ulysse Nardin, Vacheron Constantin and Zenith, in contrast with the old system whereby timers worked on commission for several manufacturers at a time. Secondly, this collection preserves the expertise on which the reputation of Swiss watchmaking is founded. Pierre-Yves Donzé adds: «For around twenty years, artisan watchmakers have been making a big comeback. Watchmaking tradition is fashionable once again. Brands seek to highlight their close links with the expertise of artisan watchmakers. It has become an important marketing tool». Are we at a point in history where the pendulum is now swinging back the other way?

November 27, 2014

News

News